As I stood atop the six-storeyed apartment

building in which my mother had bought a flat, it was easy to see the wisdom of

Rama Varma Kunjhipilla Thampuran (1751-1805). This King of the Cochin State, more

popularly known as Shaktan Thampuran or the Powerful King, had moved his

capital from Kochi to Thrissur. His wisdom in moving his palace from the coast

to a location in the midlands of Kerala was strategic – reducing his exposure

to raids from the sea by the colonial adventurers of the days. Thrissur,

however, may not have grown into a city today had Shaktan Thampuran not made

this move.

From the top of the multi-storeyed

building, I was seeing Thrissur from a height for the first time. The canopy of

the coconut palm crowns below the terrace did not hinder the view up to the

Kuthiran hills, as they stretched back into the Nelliampathies and the Anamalai

mountain block. Towards the foreground, the Kuthiran hills wrapped around the

northeastern fringes of the city and lost their height towards Wadakancherry.

In the west, the sole Vilangan hill stood like a sentinel. Historically, it has

been used as a watchtower, for its line of sight up to the Chettuva estuary leading

into the Arabian Sea.

In the western fringe, I could see the

blue-green band of the Kole wetlands and paddy fields. Fed by rivers from the

Western Ghats, this large patch of wetland in Thrissur district, is an

interface between fresh and estuarine waters as they meet with the sea. In

addition to paddy cultivation, the Kole wetlands support multiple livelihood

options for those living around it.

Though I had grown in Thrissur (and those

days Thrissur was still a town and had not been upgraded to a city), my view of

the city was always from the ground. I had grown in a single-storey cottage and

we could not see anything higher than the leaves of the coconut tree. It was

decades later, after my father’s death, my mother moved into a smaller house in

a taller building.

If my father was alive today he would be surprised

hearing about drought and water shortage in Thrissur. During the lifetime of my

father, and his father before him, in the city that the Powerful King built,

water scarcity would have been the last of all concerns. With perennial rivers

flowing by and innumerable water bodies and wetlands in an around the city, the

wells may never have dried. If that was not enough, there was copious supply

flowing through the pipes from the Peechi dam reservoir near the Kuthiran

hills.

The irrigation cum drinking water supply

Peechi project was among the earliest projects inaugurated after the Kerala

state was formed in 1956. It symbolised the aspirations and dreams of the young

state. In 1976, when my father bought the house and compound in Punkunnam,

which became our home for decades, we had enough water in our laterite-lined

well. As a backup we had water supply from Peechi reservoir.

The situation is different today. Wells are

running dry. Peechi water supply does not reach many in the city. Even if it is

does, it is not of good quality. Borewells – unheard of in Thrissur during my

growing years – are going deeper. The situation may worsen by summer, which in

Kerala is from March to May. The Kerala Government already declared the state

as drought affected in October. The southwest and the northeast monsoons were

deficit by 39%, and even after adding

the smattering of winter and pre-monsoon rains Kerala received only 1869 mm,

the lowest rainfall since 1951.

|

| Annual rainfall in Kerala from 1951 to 2016 (Source: IMD) |

But is it merely the drop in rainfall that is causing the problem? A look at Kerala’s historical rainfall data from 1951 (see graph) shows that there have been years with low rainfall, though not as low as 2016. Even 1800 mm is higher than what most parts of the country receive. For a state with 44 rivers, breaking into estuaries in the coast, there should have been some water in the reserve. Reducing forest cover, changing land use, decreasing ecological health of rivers, land filling of estuaries, increasing urbanisation and conversion of paddy fields, all ensure that the water that falls flows into the sea quickly, thus reducing the water availability in all parts of the state. This trend has been worse by the increased disregard for the environment in the recent years, and thus the impact of reduced rainfall in 2016 is likely to be felt drastically in the summer of 2017.

Interestingly, Thrissur district had the

second-highest rainfall deficit during the southwest monsoon, the main rain

bearer for the state. For Thrissur city this is being compounded by the fact

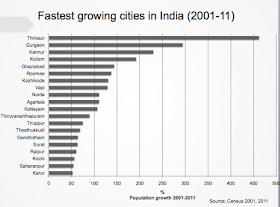

that its needs have risen. Recently, I was surprised to see the name of

Thrissur on top of a list of urban agglomerations that recorded highest

population growth between 2001 and 2011. Ulka Kelkar, fellow at the Ashoka

Trust for Research in Ecology and Environment (ATREE) in Bengaluru, had

compiled this data from the census data of 2001 and 2011. Even though partially

this can be explained by the fact that Thrissur got upgraded from a

municipality to a corporation in October 2000 and therefore adding adjoining

local bodies to the urban agglomeration, there is no escaping from the fact

that Thrissur’s population has grown dramatically in the past decade and half.

|

| The population of Thrissur urban agglomeration has grown dramatically between 2001 and 2011 (Source: Ulka Kelkar, ATREE, from Census data). |

The rapid growth in population in the

Thrissur urban agglomeration has been at the cost of its natural water sinks.

When my father bought the house in Punkunnam, there were large paddy fields not

very far from our house. Over the years, these fields were recovered acre by

acre and turned into housing plots. The huge filtration bed disappeared in less

than a few decades.

Similarly, the covered surface increased

with most of the houses paving most of their homesteads. Rainwater flows out

quickly from the city. If some of this running water could be made to walk,

then irrespective of the drought the inadequacy of water availability could

have been dealt with.

Drought in Kerala is counter-intuitive news

for the rest of the country. For the state promoted as “God’s own country” with

images of backwaters and monsoon tourism, the idea of drying wells and

dysfunctional taps do not fit in with the larger picture. The Powerful King who

built the city, could not have thought an answer for this one.

A well written and thought provoking piece. Kerala like the rest of India does depend on the rains. Does this reflect on the climate change or is it purely a cyclic phenomena.

ReplyDeleteGreat writing Gopi

ReplyDeleteThat is why Gopi should continue to write on what matters to ordinary citizens and their livelihoods. Excellent piece. So,the first culprit was Shakthan Thampuran!

ReplyDeleteI am reminded of several ground water investigations done by AFPRO in and around Thrissur including the one for Amala Cancer Hospital right at the time of laying the foundation stone. Well,our borewells served the Hospitals and drinking water needs!

Great article sir

ReplyDeleteWell done, Shakthan Gopikrishna. Point is, Trissur should do rain water harvesting like Chennai did under our great chief minister, JJ.

ReplyDeleteThank you for writing this. My parents are anticipating a water shortage in Thrissur this summer.

ReplyDelete